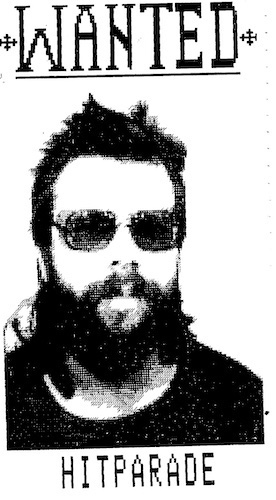

HIT PARADE

|

Hit Parade was basically a one man anarchist band, the brainchild of P. Checkoff (aka Rik O’che) a member of the Anarchist Collective in Belfast. Being a left-wing socialist Checkoff’s songs were highly political by nature and concentrated on life in N. Ireland. Subject matter ranged from the evils of television to H Blocks; the RUC to housing problems, and of course unemployment. “I wanted to make people aware that there’s more than a tribal sectarian war here, there are a lot of problems. It’s a multi-problematic place" stated Checkoff shortly after the release of the Nick Nack Paddy Wack album in 1986. Unsurprisingly, Hit Parade signed to the Crass label. Hit Parade produced electronic music made up of samples, loops and noises and were helped out in the studio by the likes of Eve Libertine, Penny Rimbaud, Jane Gregory and Flux Of Pink Indians and a host of other musicians, Checkoff said at the time “All the structure of the songs is done by me here in Belfast. But when I go into the studio in London it becomes more of a collected effort with different people putting in ideas.” The first release was the Bad News EP in ‘82. This was followed by the Plastic Culture 12” single in ‘84 and finally by the Nick Nack Paddy Wack album. The album was recorded in ‘84 but due to the financial crisis Crass were in at that time, it wasn’t released until ‘86. Penny Rimbaud and Paul Ellis produced the album. Upon the release of the E.P. Bad News, an electro-rap rant on such evils as television, H Blocks, the RUC and so on the Crass label in 1982, copies were seized by Special Branch at retail outlets, along with everything else on the Crass independent label, it managed to reach No.4 in the independent charts. Before the album was released, Channel 4 produced and screened a TV documentary on the health of women in N. Ireland. The documentary was called ‘Under The Health Surface’ and the programmes soundtrack featured the music of Hit Parade, which can be found on the Nick Nack LP in slightly different forms. The following Dave Hyndman interview was conducted by Ruth Graham for the Vacuum magazine. RG: When where you in Hit Parade? I’m not too good with dates….was it the early 1980’s? DH: It’s certainly going back a while RG: Who was involved in the band? I’ve heard that members of Crass did the backing vocals but that it was mainly you. DH: I wrote the stuff and then would go over to their recording studios and lay down the basic tracks and vocals. Penny Rimbaud produced the records and he would usually get some of the Crass members involved to augment it so while I had quite basic arrangements they would layer on a lot of stuff. It was quite symphonic. Penny was used to working with punk bands – guitarists and so forth, but he was quite creative and he started adding things. He added an opera singer at one point. RG: oh yeah, I remember that bit at the start of “Here’s What You Find In Any Prison”, in fact my brother texted me last night and said that he though that was one of the best tracks ever released on Crass records. DH: Yeah…..it went da ra da ra da ra da ra RG: Did you have to do most of the recording in England or could you do bits in Belfast as well? DH: I had to go over there. There was nothing here and nobody, as far as I could see, was interested in recording anything I did. RG: What made you interested in using synths in the first place? DH: Well, I’ve always been a keen techy and I thought that synthesizers might be a great way to reproduce the sounds that you could hear in your head. When they first came out they were touted as miraculous machines that could mimic any instrument and any sound, which of course they couldn’t, but I was convinced that they were the instruments of the future. They seemed to promise an immediate translation from your creative thoughts to the music. RG: What kind of music were you listening to in those days? DH: I’ve always been an electro fan, principally John Cage and Stockhausen. Of course people at that time were using synthesizers long before I could get my hands on them. The revolution began when they started to produce cheap synthesizers that the likes of me could afford. There were some people using synths in a pop context and other people using them in exploratory and creative ways, rejecting traditional rhythms and creating textures and so on. I was always interested in leftfield music – people like Frank Zappa and as well as that I was also interested in music that was allied to politics. The challenge was to merge the politics with the music and not to be able disengage either of them. I was told the other day that men never really listen to lyrics but that women do. In my case that could have been true but with hit parade I wanted to merge the two. If you heard the music you got the political message through the sounds as well and what the synthesizer did was to help to develop new sounds that would gel with the lyrics. RG: It’s also interesting that I’ve just known you as dave Hyndman from Northern Visions over the years but I hadn’t clicked that you were involved in Hit Parade. DH: I kept it pretty low key for various reasons. At that time in was problematic to be associated with any kind of extreme politics and the lyrics that I was writing were attacking everything and everybody. I was very angry at the time. RG: How did you link up with Crass? DH: Crass were extremely creative and they blazed a trail for activism through music. They had a great following in Belfast and we would sell their records in Just Books. At that time we also ran the A centre (or Anarchy centre) and we brought them over to Belfast. That’s how I got to know them. I think it was shortly after that that I sent them a demo tape thinking that they were the people to make it into a record…….and they did. They invited me over to Southern Studios in England to produce it. I knew that I had no chance here – I didn’t know anyone in Belfast had an understanding of synths. I was really out on a limb and most people seemed to hate the music I was making. Punk…hands on guitars….thrash….etc….all that was fine. When it came to synths it was, “Oh no these are inhuman, repetitive, beat ridden and so on”. The public didn’t like it and neither did musicians. RG: Did you do may live performances? DH: If I was going to do live stuff I had to be confident that I was free to say the things that I wanted to say. Back in the 80s some people would have found the content a bit offensive. I had to really think about where I could play and what I eventually started to do was to create my own venues. Arrangements could be problematic because synths were notoriously unreliable and a bit difficult to programme. In the end, I started to use a nice little drum machine that could hold samples and that was more reliable so I used to programme that so that I could do live stuff. When you were playing live you really wanted to punch through the rhythm – nothing too ornate – so the songs tended to be more stripped down. I think the first gig I did was in the Crescent and it was a big instrumental thing that lasted about an hour. I had asked this group called neighbourhood Open Workshops if they could create a dance around it. I asked them to theme it around a pyramid of authority so they created this pyramid and illustrated the music on stage while I played live using all the synths. It was hard work because it was constant knob twiddling and it was touch and go as to whether they would work at all. I did a few gigs in places like Giro’s and catalyst and also in Scotland in the Glasgow Tron which was nerve racking. RG: Can you tell me a bit about recording with Crass? DH: It was quite problematic bringing over all the gear because at the time I was using quite a lot of synthesizers. RG: How many synths would you need to make a recording? DH: Quite a lot….Here, Ill show you (Dave brings out some memorabilia) I managed to track down the only photo I ever had of them. These were things that were called Wasps and you could make the keyboards into polyphonic synths if you had enough of them. RG: That’s an amazing picture. They look so different – you expect them to be more compact.

DH: No, they were a nightmare. I developed particular scores for them and that was a typical score so that that I could reproduce the song. RG: It looks almost like an orchestral type of arrangement DH: It almost was – you were layering sounds and you would work very hard at trying to create that exact sound that you could hear inside your head and you were trying to preserve that sound once you got it. These were what you call pre-sets and this meant you could record all the settings on your knobs but these were the days when you had to twiddle everything – people still enjoy twiddling knobs because you can change the sound quite easily. RG: Do you think that the fact they were so cumbersome and complicated almost encouraged you to experiment more? DH: Yes, this was it. Synthesizers have these pre-sets like string sounds and bass sounds that are starting points but there’s no reason why you can’t alter them. I remember reading this article about a guy who was repairing synths and he said that when people left their synths in to be repaired most of them were kept at the pre-sets – they had never actually tried to experiment or alter the sounds that their synths could make which I thought was the whole point – to try and find different sounds. RG: That’s maybe where synths got a bad name – when they were used in a lazy way to replace instruments and make poppy sounds – at the same time there were interesting musicians using them to create a more innovative underground sound. DH: Some people tend to use synths as strings – everybody wanted strings in their albums and they couldn’t afford violins so they used synths instead. Synthesizers were incredibly innovative instruments and you could see at the time that they were going to change music forever. I remember saying that to one person who was interested in synths that one of the things that’s going to bring about the most change was the drum machine. Rap music evolved from the Roland 808 which made a very interesting sound. Technology transformed who could make records so you had all the rap artists whose essential ingredient was the voice and they used synthesizers and so on as a means of expression – they were quick to see the potential. “Here’s What You Find In A Belfast Prison” is maybe interesting because I don’t really sing in it – I rant! They used to put all these people in prison and all these things that I had said “Artists who write on walls” “kids who joyride in cars”, “those who cause embarrassment” – that was actually about mental illness in prudish times, “people framed through Diplock courts”….they were all based on actual cases. One particular artist who had written something on a wall – they put her in prison for 6 months. RG: How long was Hit Parade on the go? Did you make much more music afterwards? DH: It lasted a few albums but in the end I felt that even going over to England to records was a kind of betrayal of the self help, DIY ethos. In the end, I started up a recording studio and used that to record the next album bit it never went out. By that time things had changed a lot. People do ask me why I haven’t made more music and the answer really is that I said all I had to say in that way when I was younger. I can’t say it in the same way now. There are different ways of doing things and you change your tactics. It was hard to sell the records here – there were only one or two places that would take them and it was basically me distributing them. I must say that when I did put them in these places they went very quickly. I couldn’t distribute them in the cit centre. The thing about Crass was that they used the label to put across a lot of political content and certainly this had an impact on where the records could be displayed. The covers themselves were problematic. It didn’t matter if you were writing about housing or planning and social issues- all they could see was H Block – Republicanism – and they immediately gave it a pre-republican association RG: In a way it was all very well doing uber political stuff somewhere in England but doing it in Belfast in the early 80s would have been a completely different thing. DH: I’ll read you a wee bit from a letter Penny Rimbaud sent me, “here is the review that caused the initial interest – not much in itself but its interpretation by the gutter press as pro – republican propaganda tied in with Gerry Adam’s visit to Westminster was I think the reason that the police took an interest” They lifted all my albums and all of the Crass albums at one stage out of the record shops. RG: Do you have much of a connection with the music scene here nowadays? DH: No, I’ve never really been part of it. I’ve no interest really being part of a music scene. I was always a political being…. RG: Seething away on your own…… DH: I was very fixated with politics and music and how you could make them one thing. Musicians here seemed to be dealing with very soft politics and I felt that it should be more “in your face” and to me nobody really seemed to have that approach. Some people obviously did but I didn’t see it at that time. I think politics and music are always connected – it’s just a case of trying to understand the politics within it. I interviewed a lot of young bands when I was involved with the A centre and it became apparent to me that they actually had a hell of a lot of politics within their songs. They weren’t as propagandist as the stuff I was producing but they were still conscious of writing in a political framework. RG: I also wanted to ask you about your pseudo name at the time. P.Checkov was it? DH: I was forever using different names – it was a kind of tradition in the punk movement. It didn’t really matter to me but everybody here was being P Checked the whole time, having their movements checked and the name “P.Checkov” was just a reflection of that. RG: Thanks very much Dave.

|

|||||||

| ©

Spit Records 2025 |

|||||||