THE LURKERS

| A week or so later, August 1978, we were to off on a long sea journey, it was further than the Isle of Arran; it was our ‘tour’ of Ireland. We parked our near clapped out old van on the ferry at Swansea and waited like condemned men, unknowing and not caring for the night’s ‘voyage’ to Cork in the Republic of Ireland. The ‘management’ had told us a few weeks earlier that we had gigs booked in Cork, Dublin, Belfast and Portrush. It caused a great concern to us, fear to be honest, and I stood on that deck now that the time had come and pondered, ‘was this going to be the greatest of our ‘miss bookings?’

The Lurkers had no formal, established or recognisable ‘political’ image. Our educational credentials spoke volumes on our formal grounding and insights, explaining in part our existence in a vacuum. There were the ‘political’ groups around, loads of them, but none during that era had gone over to Belfast. When groups did later on, it was amidst a marketing tidal wave, complete with art, dress, imagery, the posing, within a framework to exploit fully the situation; but then, unfortunately, I found that is in the main what a lot of people ‘respect,’ or are conditioned to respond to. I remember thinking, ‘why us?’ We, I, was naive in nearly all matters, and ‘pop politics’ were played out by others, why were we going there? Let’s admit it, we, I, was scared.‘Belfast,’ for me, conjured up images of news stories on the television late at night with buses burning as they lay on their side. Or bleak, boring looking estates, where it’s always pissing down with rain and close up camera shots of the tape used by the police to cordon off an ‘incident’ with a couple of youngsters riding their pushbikes in the background. An image that stayed with me from Belfast was of a photograph I had seen of two young girls who had been ‘tarred and feathered’ by the IRA for fraternising with British troops. The young girls were tied to a lamp post with their heads shaved, the black gunge and muck dripping from their heads and down their faces. But what struck me as poignant about this image was that they were wearing Bay City Roller outfits. There they were, in the boots, short trousers with big flares having a wide tartan trim sown onto the bottom, a Bay City Roller scarf tied around one wrist with their faces staring up as if trying to look away from their experience. At first I thought it was rough justice for dressing like a Bay City Roller fan, until I read the article. I later thought that I often notice the clothing a person wore in grim photographs of people being killed in ‘incidents’ around the world; wondering if they ever thought that was going to be the last time that they were going to wear those shoes; or what a terrible fashion to die in. And there, the ‘innocence’ of being a young girl, joining in with ‘normal’ contemporary fashion, dressed in clothing maybe their mothers had to alter and add to in order to have the ‘Roller’ look, and now, tied against a pole. The face of ‘Eric’ smiling emptily on the tattered end of a scarf; this was never in the minds of the marketing people who pushed the Roller image.

We started the ‘tour’ with just enough money for one night’s accommodation that was in some kind of dormitory come flophouse place. I remember waking in the night with the police walking around the room, truncheons out looking for someone. Anyhow, Cork was like a set for a 1932 film; people waiting for the last dance around the walls of the hall. ‘Aliens for aliens I thought.’ Dublin was a spectacular ‘miss booking.’ It was a dyke bar that didn’t sell beer, only wine, and did they whine. They employed off duty policemen as ‘bouncers;’ Howard kicked up and was upset at their heavy handed approach, he wasn’t going to play because of the way they abused the few interested people who wanted to see us play. So they threatened him. ‘Irish eyes are smiling,’ yeah sure, the nasty miserable bastards. It must have been an arty, swanky place because Bob Geldolf turned up, I didn’t speak to him, but Howard did, telling me that he was an arrogant fucker, a university type who knew it all, and according to Howard didn’t drink.

But, all this did not matter; our real concern was Belfast. We left the motorway and entered the cramped Victorian streets of Belfast. A fine drizzle seemed to lay a seal over a place that harboured threatening intent. Shadowed by hills and the Black Mountain this forbidding place was different in all ways to what us ‘boys’ from suburbia had known or experienced. Staring through the window of our van, we searched for street names that would take us to our hotel. There were signs reflecting a life and experience that told us this place is foreign. The murals, some garish some of dark silhouetted gunmen, there were flags and messages, slogans, and names of people having a striking significance to the inhabitants of this place, which spelt ‘suffering.’ And, here ‘they’ were, whatever or however the media presented, and misrepresented the place. I looked at the people; small elderly women, bracing themselves from an hostile wind that blows wildly through the clothing and souls of those people going about their business in that town. There were different colours painted on kerbstones, words daubed like ‘H-Block;’ we didn’t know what it meant, we shared the same media, the same government, but this was a foreign land. We were lost, in all directions. An army vehicle pulled alongside us, Plug (Pete Edwards) asked one of the army blokes for directions; they all turned as one and looked at us, he came from Croydon if I remember correctly. He asked us what the fucking hell we were doing there. We told him that we were in a group; it was met with silence, “a punk group.” We gave our name, it meant nothing, the silence continued, one looked at the other, then one of them said, “you must be fucking mad.” It was strange; the faces of the young soldiers, looking out of place, to me, most of them looking like Northerners. The U.K.’s ‘cultural exchange scheme’ was an edgy one, fraught with cynicism, dissimulation, and apprehension. We booked into our hotel and experienced ‘security’ that was from a life we just simply was not used to; then was too ‘worried’ to venture around the area for a drink. Remember, at this time there was no ‘debating’ on the television, many people weren’t allowed to be on the television. There was no positive promotion of Ireland in general, no winning football team, a film industry, romantic images of ‘intellectually but tough’ young men in films, and even adverts; it had not yet become ‘cool.’ No, it was fucking cold, we were ‘out in the dark.’

That night, 23rd August we played a little place called The Pound by Queen Elizabeth Bridge; we were to play two nights. The place was packed and the reception was wild and friendly, but I thought maybe too hysterical, like people starved or denied access to participate and ‘belong’ with the flow of ‘normality.’ This over exuberance carried the night on, with us knowing nothing of the ‘troubles.’ People were asking what we thought, I tried to understand, but mostly the answer from us was about the difference in beer. An alley ran from the club to the street outside. I was standing outside by the opening to the alley talking to a bunch of young blokes before we went on. The talk was mainly about no one coming over to see them, and they spoke of things I didn’t know about and using words like ‘internment;’ I did not even know what that meant. One of the lads kicked a can into the road, just as this happened they turned and ran back up the alley. I stood there looking about myself as a sort of Land Rover pulled up sharply and these police types jumped out carrying different looking guns and took ‘positions’ of aiming rifles at roofs. I wasn’t used to seeing guns banded about in the street; it shook me, and I realised that I was in ‘that’ distant land I had seen on the television. This copper barked at me, “What is it?” A cold fear spread through me, I was numb, and didn’t have a clue what he was talking about; I think a simple smile formed across my lips. In his hammer drill tone he rasped as he repeated his question, “What is it?” He gave me a clue by nodding at the can lying in the road, which seemed to me now to have taken on an extraordinary stillness, as if this was significant in some way. I think my ‘smile’ became more ridiculous as I offered, “A can, a beer can.” His eyes had fixed themselves to a place about six streets behind my head, “Pick it up,” was his order. I stepped into the road and picked up the bloody can; it seemed to take an eternity, I could hardly move. “Put it in the gutter,” came the soothing lyrical voice from Bubbly Billy, the Bobby from Belfast. Mind, I was in no mood for micky taking at that moment; the yellow stripe running down my back was glowing to its own little inferno. He went on to ask me where I was from. I told him, and what I was doing there, thinking he might be impressed, become a bit friendly, or even apologise; but nothing. He gave a short nod to his colleagues, they jumped back in the fun wagon looking ahead grimly, or at me; and headed off, off to play at a children’s party, a Bar-mitzvah, tell jokes at a funeral, I don’t know. I can’t remember if I waved goodbye to them, but I turned, mechanically, walked up the alleyway and went back into the club. The lads that I was standing with in the street were with the promoter watching what had happened on a security screen.“Blimey, that was weird,” I said. One of the lads said, “Christ, I thought he was gonna shoot ya.” I looked at him.“That’s what they do here you know,” he said. I found the rest of the group by the bar. I walked up to Pete and told him what had happened. He turned, looking from his drink to me without expression, “Mm, well, that’s what you get for talking to people.”

We went on to Portrush for the last gig, a seaside place having echoes of Victorian Britain in its architecture; and with armoured cars rumbling lazily along, absorbing the fragrances, colours and sounds that make up the peace and idleness of a carefree holiday afternoon. A young lad joined us at Belfast, he slept on Howard and Pete’s floor in their room. He asked what living in London was like. He told me that his “ma” had bought a television; only it was wet when it was delivered to his house. In between his mum choosing the television in the shop and it being delivered, a bomb had gone off in the shop next door, or nearby, damaging the shop so they had to put the stuff outside on the pavement, and it was raining. He saw the irony of the situation and thought it funny. The next day we dropped him off in Belfast. I didn’t know if he was a Protestant or Catholic, it didn’t matter to me, we didn’t know anything about it all. But, I had gained insights, the story of his mum and the television, the images and tone in the voices had raised emotions in me. Maybe we were approached by the ‘politico’s, but it all went over our heads, seeing the dumb expression on our faces and our talk of about having a drink, told them that we were not ‘on board.’ Yet, in talking of beer, and sharing sentiments to the ordinary ‘small’ things that make up a person’s life, I look back and see at least it was real; there was no posturing and leaflet giving or speech making about subjects that affect the lives of people, and I came away from the place thoughtful and wanting to know more. I don’t think it was shared with other members of the group, but that was alright, they were not contrived, there was no ‘hidden agenda,’ they were just making of things as they can in order to get bye.

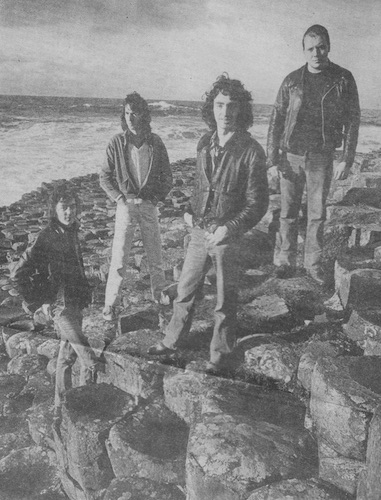

On our second visit to N. Ireland in November 1978, we again set sail from Swansea on the night crossing to Cork, this time we had a bit more money, but not much, and the company of Dave Kennedy (new tour manager) made the whole thing seem like a sinister ‘cold war’ experience. Maybe it was, but in the short time since we played there before, the place had opened up to ‘outside’ influences. We played Dublin, it was shit, and with warnings of the pseudo, ‘studenty’ pose of a place it has now become; then on to Belfast with our expectations high because of the previous good experience we had. Well, it didn’t take them long to get blasé. We played The Pound again on 23rd November and there was hardly any fucker there. Dave McCullough, a journalist from Sounds came over with Paul Slattery, a photographer. We weren’t in favour with many journalists, to put it mildly, but there were the loyal few; Mick Wall was one, and there was Gary Bushell, but my memory isn’t good enough to name the couple of others, although I appreciated their support. Dave McCullough was from the North of Ireland, or Northern Ireland, and he was a fan of the group. I think it seemed sort of surreal to him, I mean him returning to what I think he considered a provinciality of thinking, the indifference towards us and the dull nothingness of it all.“Oh, we had The Clash playing at The Ulster Hall,” or what ever the fuck it's called, “so we did,” said some smug fucker when I pointed out the difference in the amount of people who came to see us the last time we played there. So it was. The hotel had a bar, and a trad jazz band, the drummer wouldn’t let me have a go on his kit, but we had a drink and so to bed. However, our rest was disturbed by a ringing sound and a siren with a repeated spoken message to leave the room because there was a bomb scare. I was out of the bed and got dressed, telling Nigel to get up. But he wouldn’t, refusing to move he dismissed any notion of there being a bomb and went on about the London Blitz. I left the silly sod there and went out into the car park as instructed. There was Pete and Howard, with a blanket over their heads, protecting their hairstyles I thought, and somewhere, most probably on the ‘hot line’ to MI5 or the CIA was Dave Kennedy running about the place. There was no bomb, in the hotel at any rate, so we all trooped back in. I returned to my room, soaking wet, I stood looking down at Nigel, turning his head he said, “I told you so.” The next day I met up with Dave McCullough and Paul Slattery and we went on a trip to Ballymoney. The place was like a conservative middle England market town, quite twee, except for two blokes I spotted who were walking down the pavement towards us wearing balaclavas and carrying rifles. It was weird, nobody was taking any notice of them, and I deduced that they weren’t in fancy dress and collecting money to send a local child to America for some kind of surgery. I turned my body and focused on the contents of a shop, standing rigid, my gaze frozen. Through gritted teeth I hissed at Dave, “What the fuck’s going on? Who are they?” He replied in a relaxed jovial manner, “Don’t worry, they’re on our side.”‘Our side?’ ‘Our side?’ What the fucking hell did that mean? My fixed pose, and my taking an obsessive interest in the contents of the little shop did not flinch for a second as I watched in the window’s reflection the two gun carrying street entertainers pass behind me; and then, only then, did I start to breath more easily. A warm feeling surged through my body. I breathed deeply, and then stepped back sharply, Paul and Dave were watching me and also what I was looking at; in the shop window were shelves of tiny brightly coloured patent leather shoes for little girls. “Alright Esso?” Dave asked in a questioning manner. I don’t think anyone noticed. The next task was to play ‘up north,’ Portrush I think it was, but we cancelled it as Howard felt too ill”. Pete Haynes (Manic Esso) - Drummer with THE LURKERS. This is an extract from Pete's book God’s Lonely Men. You can purchase this book from his website, the address of which is listed on our links page. Lurkers Photograph © Paul Slattery

|

|||||||

| ©

Spit Records 2025 |

|||||||